Bali with Zali, January 2025

Traveling is a privilege. It broadens our perspectives, exposes us to new cultures, and allows us to step outside our daily routines. But as we move through different places, we also leave a footprint, sometimes literal, in the case of tourists treading heavily on fragile ecosystems, and sometimes figurative, through the resources we consume.

This trip to Bali with my daughter Zali was an opportunity to experience a different way of life, embrace the adventure of slow travel, and be mindful of how our presence fits into the bigger picture of tourism’s impact.

On our last day, waking up in Sideman, a hilly rural area that resembles Ubud 30 years ago, I took a moment to journal the trip. Roosters crowed, sparrows fluttered around, and I gazed over the tiled rooftops of traditional Balinese architecture disturbed only by the smell of acrid smoke. It seemed like a perfect time to reflect on our journey, and on life itself.

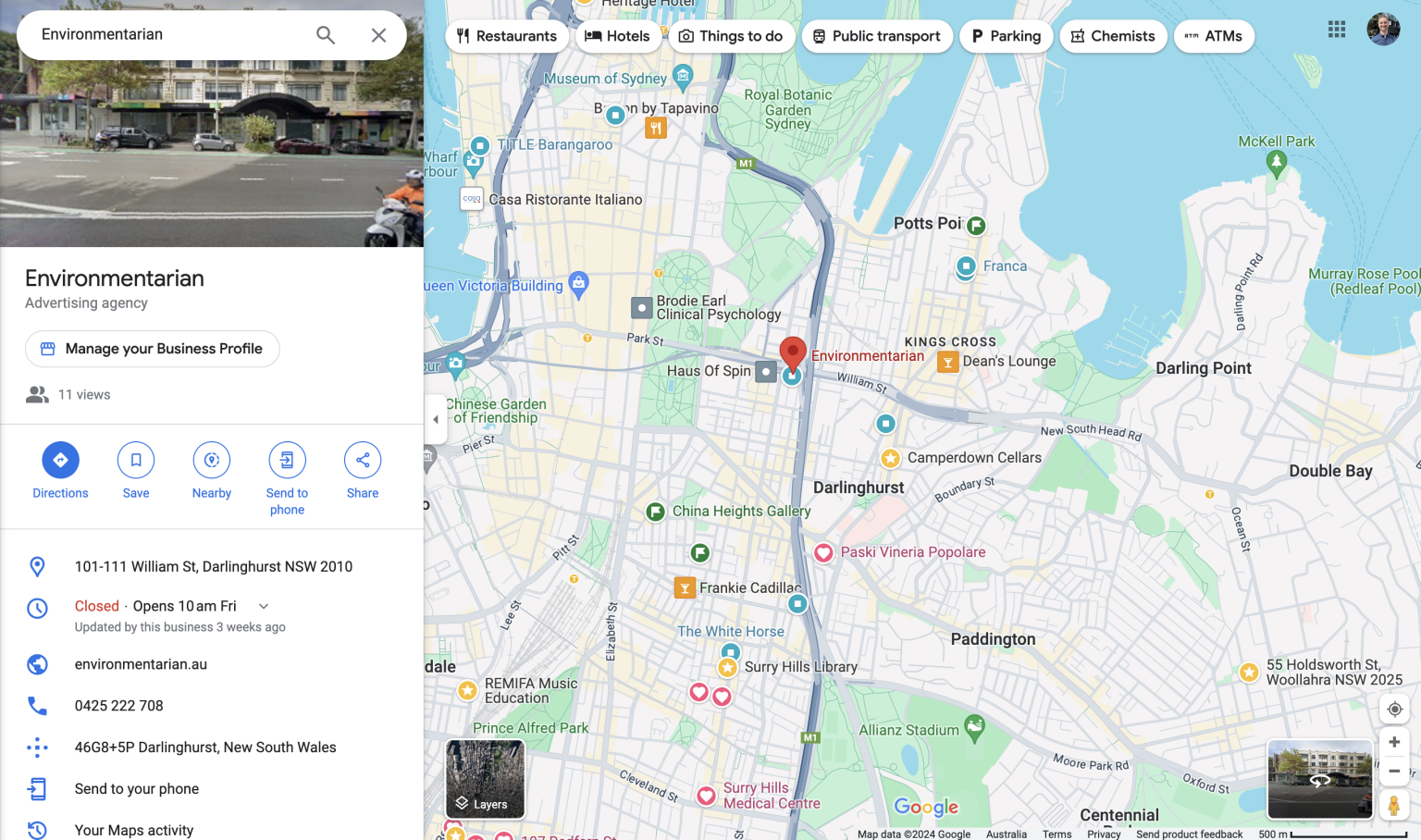

Life is good. Zali is healthy and happy, and so am I. A year ago, in January 2024, when I was here, I was recovering from overconsumption of media, alcohol, and other distractions. That trip felt like a cornerstone moment, a reset. And now, a year later, I find myself at another inflection point. Zali is about to start high school, I’m going all in with Environmentarian, and I may soon take on a major creative space project in Sydney, pending an accommodation grant decision in mid-February.

We arrived in Bali at 9 p.m., and I had pre-booked a taxi to avoid the immediate hustle of airport arrivals. The contrast between the orderliness of an airport and the lively chaos outside is always stark. “Transport, taxi?” echoed from all directions, smiling drivers eager to get a job. It’s just part of the dance of tourism here.

Settling into our first hotel, Mahe Garden in Kuta, felt familiar. I had stayed here before, and for $42 for two nights, it was unbeatable: a simple yet charming place with lush authentic Balinese gardens and reception area, and a large, lovely plunge pool. It provided a soft landing, a moment to acclimatise before diving into the adventure ahead.

As we wandered along Kuta Beach’s so-called promenade, Zali observed, “I feel sorry for these people.” The beach, once a postcard-perfect destination, was now pretty much missing what was left was strewn with debris, plastic, driftwood, the slim walking path was cluttered with sad beach shops, old plastic chairs, tired lounges and bean bags, Bintang signs – forgotten remnants of a different time. A few tourists still took surf lessons, but the scene lacked the appeal of Sydney’s pristine shores. Kuta felt like a version of itself just holding on. The heyday had passed; now, the crowds flocked to Canggu instead.

We stumbled across the Bali Bombing Memorial site and found a place for lunch. It seemed well presented at first, but missing menu items, simple things like soda water, made it feel like another example of Kuta just holding on. Across the way, outside the Ice Bar, another load of the typical Aussie tourists, who had pretty much ransacked the area over the last 30 years, hopped on a bus where you sat around a central table, peddling a ‘bike’ for no apparent reason as the bus was motorised, and drank beer. As one bus pulled out, pumping dance music, another pulled in. This kind of themed entertainment, made to draw tourists in, did little for the culture of Bali, but hey…it’s just a little harmless fun, right? Kuta still had a little bit of life, but its heyday was over.

We’d had our first Nasi Goreng, a good, simple meal for around $5, and we were ready to amble on, being mindful of our footing on the small unkempt footpaths.

Our meandering eventually led us to a hidden gem—a grand resort in the middle of Kuta’s madness. We slipped in as if we belonged, ordered fresh coconuts, and relaxed by an enormous, nearly empty pool surrounded by lush gardens, squirrels hopping through the trees. This became an unofficial mission: see how many pools we could swim in over the two-week trip.

Lembongan was different. Stepping onto Mushroom Beach, barefoot in the sand, we sought out my favourite café, where Zali ordered a smoothie bowl. Our plan was simple: embrace slow travel, eat well, swim often, and explore on foot as much as possible. We skipped the overbuilt, high-priced resorts and found a quiet, budget-friendly bungalow at Oasis Lembongan, $25 a night, a private pool, and the charm of being slightly off the main strip. Staying just outside the tourist hubs often means better prices and a chance to see the daily rhythms of local life.

One of the more meaningful encounters of the trip was meeting Petra, mother of a family friend and well respected Bali expat, a remarkable woman who has spent the last 20 years building an eco-community in Bali. Petra is now set up in Saba where we had deep conversations about sustainability, environmental education, and her latest initiative, Eco Games, a startup dedicated to engaging people in environmental issues through board games. Her passion was infectious, and I offered to help where I could, blending my own work with hers to explore potential collaborations.

We also took a guided walk through the agricultural hills of Sideman with Wayan, a first-born son and now an older man with vision issues. Whilst it was super picturesque the plastic was still everywhere especially in the waterways. Wayan explained that they do clean it up from the fields…and burn it. That was the acrid smell from the smoke I watched above the buildings this morning. Wandering through terraced rice paddies that had a permaculture feel with mixed vegetables and organic weed suppression, composting, surrounded by banana, papaya, and coconut trees, it was a beautiful reminder of the balance between traditional ways of life and the modern changes creeping in. These slower, grounded moments connected us more deeply to Bali beyond the tourist hotspots.

Sustainable Travel: A Delicate Balance

Check out the engaging video that reflects on the beauty traditions and challenges…

Other sustainability measures we took

- Carbon offset our flights by opting in when buying the tickets. An extra $10 approximately.

- Did a lot of walking, minimising motor scooter use.

- Rented a push bike in Sanur, where we stayed for five days, and walked from the ferry to our hotel. No motorised transport for five days, and we still had a great time.

- Ate in local warungs, refusing plastic straws whenever possible.

- Asked the laundromat to return our clothes in the sarong they were wrapped in instead of a single-use plastic bag. Zali noted how neatly they wrapped it.

- Mostly drank coconuts (compostable) and filtered water (reusable).

- Minimal meat consumption.

Sure, there is probably much more we could have done, but this was also a holiday for myself and my daughter. Not an eco-warrior adventure. Life is about balance.

Closing Reflections

Travel, at its best, is about connection. With people, with places, with ourselves. It’s about experiencing both the joy and discomfort that come with being in a foreign land—navigating language barriers, witnessing cultural shifts, and acknowledging the impact we leave behind.

Bali, for all its beauty, sits at a crossroads. Mass tourism has brought prosperity but also pollution, overcrowding, and lost traditions. Taxes and tariffs aimed at improving infrastructure like water and waste management are being mismanaged. As travellers, we have a responsibility to tread thoughtfully, to support businesses that reinvest in the community, and to be mindful of how we engage with the places we visit.

This trip reinforced something I’ve long believed: sustainable travel isn’t about perfection. It’s about small choices, where we stay, how we move, who we support. It’s about knowing when to care, when to accept, and when to act.

As we packed our bags and crossed our fingers that our booked transport would actually show up, I felt content. The adventure had been worth every challenge. Now, back to Sydney, to high school transitions, new projects, the potential of exciting collaborations, and the hopeful anticipation of securing the accommodation grant that could be a game-changer for my next steps. 2025…let’s do this!

Further Commentary…

Jeremy:

Hey ChatGPT I recently read that Taxes and tariffs aimed at improving infrastructure like water and waste management are being mismanaged in Bali. Thoughts?

ChatGPT:

Yeah, Bali has been grappling with mismanagement of infrastructure funds for a while, and it’s a big problem considering how much revenue tourism brings in. Taxes and tariffs—especially those from tourists and businesses—are supposed to go toward things like waste management, clean water access, and road improvements. But corruption, bureaucratic inefficiencies, and poor planning often mean the funds don’t go where they should.

Waste management is a perfect example. Despite multiple initiatives and even bans on single-use plastics, Bali still struggles with overwhelming waste, much of it ending up in rivers or the ocean. Tourists see the beaches being cleaned daily, but that’s just surface-level maintenance—landfills are overflowing, and recycling infrastructure is weak.

Water is another issue. With luxury resorts, rice farming, and growing local populations all pulling from the same aquifers, Bali is facing freshwater shortages. Some villages already rely on imported water, even though tourism taxes could, in theory, be funding sustainable solutions.

It’s frustrating because the potential for better infrastructure is there. The government has recently introduced a $10 tourist tax, supposedly for environmental and cultural preservation, but whether it actually makes a difference remains to be seen.

If Bali wants to sustain tourism long-term, it needs real accountability for these funds—transparent spending, investment in circular economy models, and support for local waste and water initiatives instead of just patchwork fixes. But as with many places, the politics of development often get in the way of real progress.